By MORDECAI SPECKTOR

Łódź, Poland — Milena Wicepolska, our tour guide on a lovely Sunday in Łódź, led us into a courtyard of a nondescript building in the center of the city. Then we passed through into another courtyard where cars were parked and saw a derelict synagogue in a corner. A scrub tree was growing from the edge of its roof.

There were four large synagogues in Łódź prior to the Shoah, Milena told us. And there were hundreds of smaller prayer rooms.

“Many synagogues were destroyed,” she commented, as we gazed upon the Polish city’s last surviving shul, “but this one was destroyed by time.” It’s a husk with six-pointed stars still decorating the windows.

We — my wife, Maj-Britt Syse; my son, Max Specktor; and I — had left Warsaw earlier in the morning of July 11. Grzegorz, our driver from Taube Jewish Heritage Tours, picked us up near our apartment in his immaculate Mercedes SUV. Through the day he kept the car stocked with cold bottles of spring water. Łódź (pronounded “Woodge”) lies 75 miles southwest of Warsaw, so we enjoyed a ride of an hour and 20 minutes each way. Tall barriers blocked our view of the countryside on various stretches of the highway.

When we arrived, Milena, an historian who is writing her master’s thesis on the Łódź ghetto, met us in the lobby of a boutique hotel in the restored Manufaktura, a sprawling cotton mill from the 19th century that was owned by Izrael Poznański, one of the three “Kings of Cotton” in the city.

The 170-acre Manufaktura, in recent years, has undergone mixed-use development, including a multiplex movie theater, shopping mall, three museums and restaurants. We enjoyed lunch there in a Polish restaurant; I had turkey livers in a sauce of cherries and apples, and placki, Polish latkes.

Next to the red-brick Manufaktura is a palatial home that covers two city blocks, the Poznański residence. It’s being redeveloped as a municipal museum. There are many stories to tell about Łódź, which became an important textile manufacturing center in the 19th century. Its population of Poles, Jews and Germans was only 800 in 1800, but it increased rapidly as the textile business boomed.

Łódź once had a large vibrant Jewish community, the second largest in prewar Poland, that included artists and Yiddish writers and playwrights. Yung-yidish was the first “Yiddish artistic avant-garde group in Poland,” according to an account in the online YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. The group, which formed in 1918, soon published a journal titled Yung-yidish.

Milena mentioned that David Beigelman (1887-1945), a violinist, orchestra leader and composer of Yiddish theater music, lived near the Poznański mansion. During the Nazi occupation, in 1940, Beigelman conducted a symphony orchestra in the Łódź ghetto. He was deported from the ghetto to Auschwitz, where he died in 1945.

Today the center of Łódź is a mixture of inhabited and derelict buildings. Milena said that some of the old buildings collapse from time to time. Others collapse while undergoing renovation. She said that World War II movies have been shot in Łódź, which offers a bombed-out look on certain blocks. Generally, capital is lacking to restore many of the crumbling 19th century buildings.

Our walking tour took us to the area of the former Łódź ghetto, which is sometimes referred to as the Litzmannstadt ghetto. Litzmannstadt is the name the occupying Germans gave the city, after Karl Litzmann, the German general who captured Łódź in World War I.

Unlike the Warsaw ghetto, which was reduced to rubble by the Nazis, the buildings in the former Łódź ghetto are still standing. Milena held up archival photos depicting a church and a large plaza, and we could recognize the area in front of us. Nearby stood a large red brick building called the “Red House,” a former church parish house that was commandeered by Kripo (Kriminalpolizei), one of the Nazi police agencies involved in stealing the assets of Jews.

At the Radegast train station, where Jews in the ghetto were shipped to extermination camps across Poland and which is now a memorial to the victims, we saw a photo from the Holocaust era of Chaim Rumkowski, head of the Judenrat, the Jewish Council in the Łódź ghetto, talking with Hans Biebow, who headed the Nazi administration of the ghetto. Rumkowski, an imperious character, coordinated transports from the ghetto to the death camps with the Nazi overlords. The first transports carrying some 71,000 Jewish victims, in 1942, went to the Chełmno extermination camp, which had opened in 1941.

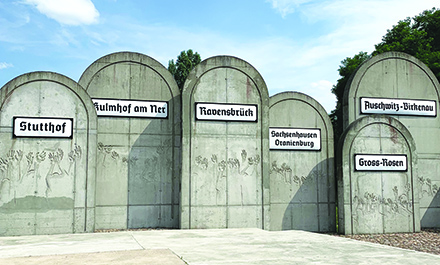

There are replica cattle cars at the Radegast train station. Outsize tombstones bear the names of the death camps where the Jews, and some Roma, were transported and murdered. The memorial complex includes a miniature-scale model of the Łódź ghetto and a tunnel which evokes the path of the trains that transported Jews to the death camps.

Also, Jews from elsewhere in Poland and Europe arrived at the Radegast station and were interned in the ghetto. Those arriving in the Łódź ghetto were in for a shock. “Living conditions in the ghetto were horrendous,” according to the online Holocaust Encyclopedia of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “Most of the quarter had neither running water nor a sewer system. Hard labor, overcrowding, and starvation were the dominant features of life. The overwhelming majority of ghetto residents worked in German factories and received only meager food rations. More than 20 percent of the ghetto’s population died as a direct result of the harsh living conditions.”

Our final stop on Sunday was the Łódź Jewish Cemetery, also known as the New Jewish Cemetery. When we pulled up to the cemetery, Milena pointed out Paweł Kulig, who chairs the Guardians of Remembrance Association. The group’s volunteers, non-Jewish Poles, restore Jewish cemeteries in Poland that have fallen into disrepair. A contingent of Kulig’s group had been working in the immense Łódź Jewish Cemetery that day.

The cemetery covers around 109 acres; a broad central avenue runs through the cemetery, which looks like a forest around the periphery. The dark green woods with headstones everywhere and every which way spooked me for a moment. Milena assured me that there was nothing to fear — she had been alone in the cemetery many times.

Of note in the cemetery was a mammoth mausoleum for the Izrael Poznański family. The inner dome of the structure features a colorful mosaic with trees and a Star of David at the top. Milena had mentioned that the Manufaktura had gone bust during World War I, and she pointed out a very modest headstone near the mausoleum, the grave of one of Poznański’s sons, who had been reduced to penury. Milena also showed us the memorial for Izrael Lichtensztain, a leader of the Bund, the Jewish socialist organization, in Łódź. His memorial features large stylized Hebrew characters that spell out “Bund.”

Grzegorz drove us into the center of town and we parted ways with Milena. In Warsaw that night, I made the scene at Klub Stodoła, a spacious jazz concert hall. The John Patitucci Trio, with Brian Blade on drums and Chris Potter on sax, was in town for the Warsaw Summer Jazz Days festival. It was their first gig since being sidelined by the pandemic and they were in top form.

(American Jewish World, Sept. 2021)