By MORDECAI SPECKTOR

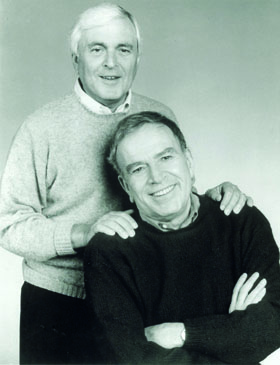

John Kander traveled from his home in New York City to Minneapolis last week to help tune up his new musical, The Scottsboro Boys, at the Guthrie Theater. Kander, half of the famed songwriting team of Kander and Ebb, has enjoyed Broadway success for his musical contributions to shows including Cabaret, Chicago and Kiss of the Spider Woman. The tunesmiths also wrote “New York, New York,” a song identified with Frank Sinatra.

The Scottsboro Boys, which is being previewed this week and opens Aug. 6 at the Guthrie, before its Broadway opening at the end of October, represents the last collaboration between Kander and his musical partner Fred Ebb, who died in 2004.

During a recent telephone interview with the Jewish World from his home in New York City, Kander discussed his storied career, the origins of his current show, and the amazing success of Jews in the realm of American popular song.

In the way of background, the Kander and Ebb collaboration spanned four decades. In addition to tunes for musicals, TV and the movies, the duo wrote songs for Barbra Streisand (“My Coloring Book”) was an early hit for the songwriters and earned them a Grammy nomination), Liza Minnelli, Sinatra and others.

Kander and Ebb’s first Broadway show was Flora, the Red Menace, in 1965, which was produced by Hal Prince and directed by George Abbott. That was followed by, among other shows, Cabaret, for which Kander and Ebb won the Tony Award for music and lyrics; The Happy Time; Zorba; Chicago; The Act; Woman of the Year (Tony Award for music and lyrics); The Rink; Kiss of the Spider Woman (Tony for music and lyrics); and Steel Pier.

With the death of lyricist Ebb, Kander was left with several projects in various stages of completion, including The Scottsboro Boys.

Kander said that he and Ebb were looking for a new project in 2002; and — following the shows Flora the Red Menace and Steel Pier — focused again on the ’30s, the Depression era in America.

“There was an atmosphere there… it seemed there was more exploring to be had,” Kander remarked. “And we stumbled on the story of the Scottsboro Boys. Being the oldest member of the group, I’ve always been able to say that I remember when that story was forgotten.”

The actual story of the notorious miscarriage of justice known as the case of the “Scottsboro Boys” began on March 25, 1931, when a fight broke out between young whites and blacks aboard a Southern Railroad freight train. Nine black youths were arrested and taken to Scottsboro, Ala., where they were charged with raping two young white women. A lynch mob formed outside of the county jail; and, at the request of the local sheriff, Alabama Gov. Benjamin Meeks Miller had to call out the National Guard to protect the defendants.

On March 30, a Scottsboro grand jury indicted the nine, who were all tried, convicted and sentenced within a week and a half. Eight were sentenced to death, and one to life imprisonment.

News of the speedy trials of the young defendants spread throughout the country. Progressive national organizations, including the NAACP and the International Labor Defense, took up the Scottsboro case, and raised money for legal appeals. By late June, the executions of the defendants were stayed pending an appeal to the Alabama Supreme Court.

“It was a story that took place in the Depression, and in a racially and ethnically divided country,” Kander remarked, regarding the sordid chapter of American history. “The story sort of haunted us…. Then, finally, we decided that we really wanted to tell this story. The only trouble was we couldn’t figure out how to tell it; because it’s not like a neat little play with a few characters and a denouement. It’s a story that went on for well over a decade and had lots of characters in it. Then we hit on the idea of using the old-fashioned minstrel show as a form.”

Kander noted that he and Ebb chose the minstrel show framework “not just because of the racial implications” in the history of that entertainment, but because the flexible form — with the interlocutor and endmen — allowed for songs, stories and “dumb jokes.”

“Once we found that form, then it began to write itself rather easily,” the 83-year-old composer recalled, regarding the songs and structure for The Scottsboro Boys. “We were well into it when Fred Ebb died, which is 2004; then I had to think things over. He had been my collaborator for 40 years; and, basically, I had never really worked with anyone else.”

Asked if someone came in as a lyricist to finish the songs, Kander said, with a laugh, “That’s me… I gave it a shot.” So, he wrote the lyrics that were needed. “I knew more about Fred’s style than anyone else.”

The show, which had an acclaimed run off-Broadway, is directed and choreographed by Susan Stroman, of The Producers fame; the book is by David Thompson.

In a certain sense, the songs for The Scottsboro Boys have their origin in Kander’s time at Camp Nebagamon, which he attended back in the 1930s. The campers were mainly Jewish boys from the Midwest — Chicago, St. Louis and Kander’s hometown, Kansas City.

“The counselors’ show was, in fact, a minstrel show,” he said. “In its own kind of sloppy way, it followed the basic rules of minstrel shows… and without any of us, of course, being sensitive about the racial implications… I guess a certain sound of all of that still rings in my ears.”

Asked if the show draws on blues music, Kander replied, “There’s some blues in the score; but there’s a lot of a ragtime feeling, I think. I didn’t set out consciously to do one or the other.”

In addition to the Jewish songwriting team of Kander and Ebb, The Scottsboro Boys has a major Jewish connection, in the character of a famed New York lawyer who handled the second trial, and ultimately argued the case before the U.S. Supreme Court.

“Along with the racism of the period, there was tremendous anti-Semitism, particularly in the South,” Kander explained. “The lawyer from the East, Samuel Leibowitz, who had never lost a case — he was a really major figure — came down [to Scottsboro], pro bono, to take on their case. He got to the point where it was obvious that they were not guilty, that the whole thing was a frame-up; and they lost. They lost, some people feel, in great part because his name was Samuel Leibowitz.

“There is a song in the show — which actually is a blues song — sung by the prosecuting attorney, which is as bald, full-out an anti-Semitic song as you can conceive. It’s shocking when you hear it,” commented Kander, regarding the song titled “Financial Advice.”

Over the years I have asked musicians and songwriters — Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, Neil Sedaka, Michael Feinstein et al. — about their thoughts on why Jews are preeminent in the world of American popular song. Kander said that he has thought about the subject and read some things.

“In the East, the general feeling is that it all comes from the tradition of Yiddish theater,” he responded. “Music was used to tackle all kinds of subjects.”

Kander concurred that Jews — from Irving Berlin to the Gershwins and Bob Dylan, a Hibbing, Minn., native — have played an amazingly prominent role in popular song. Like sports, perhaps, show business has provided an opportunity for Jews, and other emerging minority group members, to make their mark.

“The eastern group, the New Yorkers, it’s pretty easy to make the case for the roots in Yiddish theater. In Kansas City and Hibbing, it’s not so easy,” Kander concluded.

***

Kander and Ebb’s musical The Scottsboro Boys opens Aug. 6, and runs through Sept. 25, on the McGuire Proscenium Stage at the Guthrie Theater. For tickets, call the Guthrie Box Office at 612-377-2224, toll-free 877-44-STAGE, or go and online at: guthrietheater.org.

(American Jewish World, 8.6.10)