Reviewed by NEAL GENDLER

Even the Nazis were surprised at how quickly and easily they took over Germany.

In Hitler’s True Believers, Robert Gellately shows that Adolf Hitler did not drag an unwilling nation into militaristic, anti-Semitic dictatorship. A November 1933 plebiscite on Nazi rule drew 95.1 percent in favor.

“No historian believes that Germany was already so homogenized that all ‘yes’ voters had exactly the same motives or meanings,” Gellately says. Motives varied from “ecstatic agreement to sullen assent.” Berlin voted 10.8 percent “no,” Hamburg 13 percent.

“No historian believes that Germany was already so homogenized that all ‘yes’ voters had exactly the same motives or meanings,” Gellately says. Motives varied from “ecstatic agreement to sullen assent.” Berlin voted 10.8 percent “no,” Hamburg 13 percent.

But “the larger picture people faced from 1933 onward was the shocking suddenness with which Hitler, the National Socialists and their allies changed a parliamentary democracy into a one-party dictatorship, and an open civil society into one that became increasingly closed,” Gellately says.

He explains how this happened in one of Europe’s most educated and cultured nations, showing that many of the early Nazi leaders shared Hitler’s ideology before they’d met or heard him or read Mein Kampf.

They were angry about Germany’s defeat, the lopsided Versailles treaty, the Weimar Republic’s democracy and social chaos, the 1918 revolution and runaway inflation.

Most hated Jews, saying they should be expelled or even killed. Fiercely anti-Communist, many blamed Jews for Russia’s Bolshevik revolution, which became a theme in Hitler’s speeches. Some were members of the Freikorps (Free Corps), a right-wing miltia of 250,000 to 400,000 shut down in 1920.

The first half of True Believers examines how ordinary people became or supported Nazis — won over by ideas, employment, housing and rallies and parades across Germany. The second half traces “how the regime applied its teachings to major domestic and foreign events, racial persecution and cultural developments … and how people reacted or behaved,” says Gellately, history professor at Florida State University and author or editor of 10 previous books.

True Believers begins with Hitler’s ideological development, creation of the NSDAP (National Socialist German Workers Party) and his tortured explanations of combining nationalism and socialism without Soviet-style seizure of private property.

This occasionally bogs down a bit, and the 332 narrative pages could have used more-frequent mentions of the year under discussion, but True Believers is compelling, sometimes fascinating, reading. And it is very much about hatred and persecution of Jews.

“Hitler’s racism was integral to his doctrine,” with anti-Semitism at the core of his worldview, the Nazi movement and the regime, Gellately says. In Hitler’s prospering, strengthening Germany, “there would be no place for Jews,” who in 1933 numbered 449,682 of Germany’s 65.2 million people.

“The dramatic turn in Hitler’s life, as for much of Europe, came in August 1914,” with World War 1, Gellately says. In a 1915 letter, Hitler said that when he and his comrades returned home, “they hoped to ‘find it purer and cleansed of foreignness.’” His first known political speech came in 1919, Gellately says, and although it has been lost, “an army report said [it] had touched on capitalism and had such a marked anti-Jewish tone that it could be deemed highly inflammatory.”

Gellately divides the Nazi phenomenon into topics, causing some back-and-forth in time and a bit of repetition, but illustrating how themes interlocked. Chapter titles include “National Socialism Gains Power,” “The Quest for a Cultural Revolution” and “Nationalism and Militarism.”

A chapter is devoted to racist ideology, but grotesque hatred of Jews — and actions to exclude, vilify and impoverish them — runs throughout the book.

Hitler emphasized Volksgemeinschaft, “bringing the nation together into a community of the people,” Gellately says. Its slogan was “the common good before individual good.” Jews were not “the people,” but vermin.

Although 25-page “War and Genocide” covers 1939 to 1945 in broad terms, with occasional horrifying details, the book emphasizes how the Nazis gained office, won over the population and swiftly injected their ideology into almost all of German life, from art to agriculture and school to marriage.

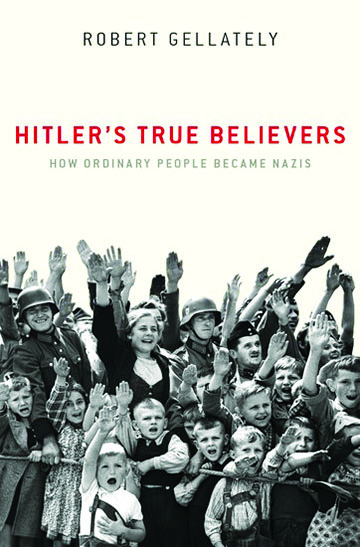

True Believers offers larger type than some Oxford books, but pages are unrelieved by subheads or photos. I would have suggested at least half-column headshots of principal characters at first mention. There’s room: At the end are 16 blank pages. Sixty-seven pages of source notes are followed by a 27-page bibliography and mercifully, a 15-page index, if in eye-test type.

Perhaps Gellately’s ultimate explanation is in the first paragraph of his conclusion: “The National Socialist ‘big idea’… was constructed out of elements of radical nationalism, a variety of socialism, and passionate antisemitism….

“This cluster of ideas proved to be successful precisely because they were unoriginal and were already imbedded in Germany’s political culture.”

***

Neal Gendler is a Minneapolis writer and editor.