Reviewed by NEAL GENDLER

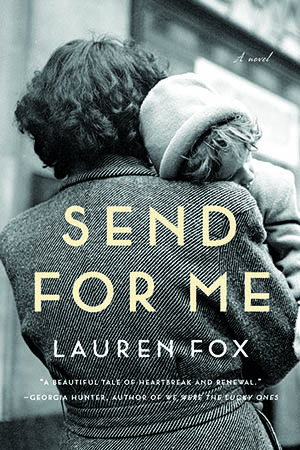

Lauren Fox’s sad, engaging Send for Me deftly reverses familiar Shoah stories.

Fox writes from the other side of heart-rending survivor accounts and diaries of victims that are made sadder for knowing their lives soon will end.

Send for Me is a multigenerational tale of love, relief and despair of a young Jewish refugee whose parents are trapped in Germany.

It’s told mostly through the life of Annelise, the only child of hard-working Julius and Klara, whose successful bakery in Feldenheim produces delicacies with tongue-twisting names.

It’s told mostly through the life of Annelise, the only child of hard-working Julius and Klara, whose successful bakery in Feldenheim produces delicacies with tongue-twisting names.

Snippets from Klara’s letters to Annelise in Milwaukee are a running counterpoint, revealing increasing hardships, longing for her daughter and granddaughter, and desperation to emigrate.

Send for Me is “historical fiction,” a troubling genre because of difficulty discerning history from fiction. Fortunately, Fox, a University of Minnesota MFA graduate, focuses on the emotions of people living that history. In a note at the end, she reveals what’s fact.

We meet Annelise as an inquisitive young child. Her parents, like many Germans Jews then and many American Jews now, are deeply Jewish culturally but unobservant.

Brilliant but messy Annelise is prodded and scolded into improvement by Klara, who, Fox writes, “was training Annelise to function without her…that is the project.” Fox says: “A mother teaches her daughter to perpetuate the tedious rituals of her own imperfect life…instilling in her child the virtues of order.”

As a teen, Annelise serves customers. They include Walter, a charming, prosperous shoe-store owner very attentive to his stunning, aloof wife.

We follow Annelise through adolescence and the Nazi takeover, its “Don’t Buy from Jews” campaign slowly strangling the bakery, and into young womanhood and marriage at 21 to now-divorced Walter, 10 years older, his Goldmann’s Shoes also faltering.

They have a child, Ruth, and during Annelise’s pram-pushing walks in a city of hateful gentiles and Nazi thugs, we learn that Jews are forbidden parks, public benches, restaurants, typewriters and citizenship.

About 1938, Walter, Ruth and Annelise sail for the United States, confident her parents soon will get entry visas and follow. But as conditions worsen, they remain trapped in the State Department documentation blizzard designed to keep Jews out.

The three go to Milwaukee, where Walter sells shoes at Gimbel’s and Annelise takes in laundry and cleans houses.

Ruth marries, but she and husband Mel appear lightly, perhaps a vehicle to get to Annelise’s granddaughter Clare. She’s 28, educated, working at an uninspiring job and attending girlfriends’ weddings.

As a little girl, “Clare had spent long afternoons with her grandparents” while her parents worked. Walter and Annelise diverted her playground requests with indoor activities. Now, as “loneliness accrued around her,” she wonders if some of their sadness had lodged in her.

Helping clean Ruth’s basement of boxes stored after Annelise’s death, Clare discovers Klara’s letters.

“Without telling her mother [Ruth], who was too sad for it, Clare paid to have the letters translated. … She sat on the lumpy green futon couch in her little apartment on a Sunday and read them, start to finish, from 1938 to 1941.”

Klara became real: “She was prickly, desperate. Furious. Lost. Clare, her namesake, lived ordinary days.” Until the letters.

“Someone had to find them. How else would they be here, telling their mundane and anguished story. … From the blankness of their vanished years…the dead rose up and made themselves heard.”

Such wonderful turns of phrase abound. For example, unmarried Annelise is “pulsing with the pain of being unpicked,” as is Clare. Aboard ship, Annelise is “suspended between heartbreak and possibility, regret and relief.” Mensch Walter “is nobody’s misfortune.”

In an American resort cabin, Annelise smells the stove’s history of bacon. “She has never kept kosher but there are some foods so wrong to her that they might as well be poison.”

And Mel mows, wearing “a red T-shirt, yellow Bermuda shorts and black dress socks. He looked like the flag of a small European country.” That flag would be Belgium’s, but perhaps not coincidentally, also Germany’s.

There’s a bit too much foreshadowing, and overdoing about “great, gasping, winged monsters of ruin,” but my only complaint is the abrupt switches of decade and nation, requiring several sentences to figure out. They follow unnumbered pages — maddening to a reviewer — and italicized snippets of Klara’s letters.

Send for Me is beautifully done. While not necessarily a “women’s book,” whatever that is, its men are supporting actors for acute observations that could come only from a sensitive and articulate woman who has a daughter; Fox has two.

***

Neal Gendler is a Minneapolis writer and editor.