Reviewed by NEAL GENDLER

For such a slender book about someone dead for 88 years, Sarah provides a surprisingly vivid feel for one of the most adored, most remarkable women of the 19th century.

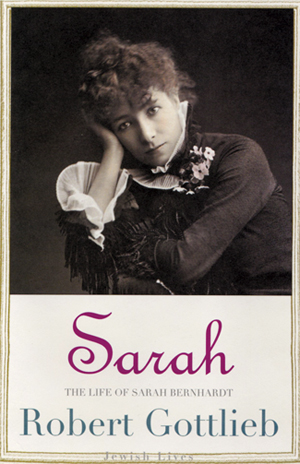

In just 256 generously illustrated pages, author Robert Gottlieb paints a strong portrait of Sarah Bernhardt, the theatrical phenomenon who enthralled audiences across much of the globe, their fascination enhanced by what for its time — or even ours — was a lavish and loose lifestyle.

Many biographical details are speculative, with unreliable accounts coming from friends, enemies and Bernhardt herself. Gottlieb writes: “She was a compete realist when dealing with her life but a relentless fabulist when recounting it.” Yet the book has reliable accounts of her theatrical prowess, taken from sometimes effusive reviews. It also quotes from negative reviews, some of them vile with anti-Semitism.

Gottlieb’s narrative is casually erudite, yet very accessible, as one might expect from someone who has been editor-in-chief of Simon and Schuster, Knopf and the New Yorker. In addition to photos of a gorgeous young Bernhardt and of many of the people in her life, 16 pages show her in starring roles as diverse as Phaedra and Hamlet.

Waiflike Bernhardt, a fiery redhead of frail health raised by a “distant and disapproving mother” and no father, lived a life of defying convention. Loathing some of her training at Paris’ Conservatoire, she decided to become the world’s greatest actress. She succeeded by using “a voice of gold,” creating her own electrifying style and applying enormous intensity to her craft. Even in her later years, colleagues testified to “her almost rabid attention to detail, her constant rethinking of her roles, and her insatiable energy.”

That insatiable energy went beyond the stage, what Gottlieb calls “her unquenchable need to be the center of attention” increasing her celebrity. Her life was a drama: important career help from her mother’s contacts; a practice of bedding her leading men; an apparently little-concealed parade of lovers; and no concealment at all of her out-of-wedlock son. Subject of her utmost devotion and indulgence, he often accompanied her on tours and at receptions. Apparently, even in the Victorian age, super-stardom could perfume away the scent of scandal.

She toured widely to acclaim, even nine times to the Americas although speaking only French. She became a sculptor and writer and created her own Theatre Sarah Bernhardt, spelling her name across the façade in 5,700 light bulbs. Fiercely patriotic, she endeared herself to her countrymen during the Franco-Prussian war, turning a closed theater into a military hospital, stocking it with supplies and tending the wounded.

Bernhardt, likely born in 1844, was baptized at her father’s insistence just before turning 12 and attended a convent school for six adolescent years. She publicly professed Catholicism but practiced little religion, called herself “a daughter of the great Jewish race” and defended Dreyfus. Her Jewishness runs like a slender thread through much of Gottlieb’s account.

Gottlieb is a smooth writer, blessedly restrained with French phrases. But while identifying Alexandre Dumas or son as “Dumas père” and “Dumas fils” is a bit charming, less so is identifying some important characters without first names, using instead untranslated titles, as in “le duc de” and “le conte de.”

Despite such quibbles, Sarah is an enjoyable, easy read, using the words of the actress and her contemporaries to color in the life details, mannerisms and fierce determination that explain her fame.

I can’t say that Sarah leaves me feeling quite as if I knew her, but it very much makes me wish that I had.

***

Neal Gendler is a Minneapolis writer and editor.

(American Jewish World, 2.18.11)