Reviewed by NEAL GENDLER

Otto Silbermann’s unusual flight from Nazi pursuit ends in a way too unexpected to reveal.

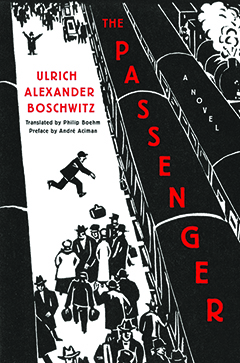

Otto is the protagonist in The Passenger, a rediscovered, astonishingly penetrating and prescient 1939 novel by Ulrich Alexander Boschwitz. Son of a Protestant woman and a Jewish dentist and businessman who became Christian and died before the author’s birth, Boschwitz dashed off the draft over four weeks in England.

(The author was a first cousin to Minnesota’s former U.S. Sen. Rudy Boschwitz, although Rudy says they never met. Rudy said last month that Ulrich’s father was Sally — pronounced “Zollie” — the fifth of five boys. Rudy’s father was Eli, the fourth son, who the day Hitler became chancellor told his wife: “We are leaving Germany forever.” They came to the United States in 1935, and Rudy later met and helped support Ulrich’s sister, Clarissa, who became a Jew in Israel.)

The author brings us deeply and convincingly into the distressed mind of a desperate Jewish businessman in 1938 Germany.

Or so Otto was. Now, he’s “something different because I am a Jew,” he says. “What am I really? A swear word on two legs, one that people mistake for something else! I no longer have any rights, and it’s only out of propriety or habit that so many act as though I did.”

It’s also out of Otto’s well-dressed physical appearance: He doesn’t look Jewish, whatever that means. Jews say he looks Aryan. In what way, we’re not told, but it’s his biggest advantage.

His second biggest is that he has money; a desperate deal with an employee-turned-partner because he’s Aryan has left him with 41,500 marks in cash. Otto carries most of it in a briefcase as he seeks to avoid capture by riding trains, one after another after another.

He regrets not having fled Germany when it still was possible. Now, other countries don’t want to let Jews in.

“I’m a prisoner,” he thinks. “For a Jew, the entire Reich is one big concentration camp.”

His son Eduard is in France, trying to get entry papers for Otto and wife Elfriede. In 1938, France seemed like safety.

The story is told through Otto, mostly in his tormented thoughts while passing as a gentile, yet ever alert and trying not to be conspicuous. The money buys restaurant meals, train fare and an occasional edgy night’s lodging, but it won’t solve his problem.

He thinks: “I have to get out of Germany! Only there’s no place to go! To make it out of here, you have to leave your money behind, and to be let in elsewhere, you have to show you still have it.”

Otto’s flight begins with stormtroopers beating at the front door of his comfortable apartment. His Christian wife of 20 years helps Otto to escape out the back, before the Nazis trash the place, brutally beating a gentile visitor they mistake for Otto. But he has nowhere safe to stay.

So he rides trains.

“The fact is that I have emigrated… to the Deutsche Reichsbahn,” he jokes to himself. “I am no longer in Germany. I am on trains that run through Germany. That’s a big difference.”

The Passenger jars us with Germans’ casually expressed Jew hatred. People Otto knows avoid him, places he used to go ask him to leave. Any German could be his enemy. For this he fought in the Great War?

At a familiar hotel, he asks a waiter about the missing concierge.

“He was arrested this afternoon. He was a Jew, after all,” the waiter says. Otto thinks: “Obviously, the waiter found this explanation sufficient.”

Boschwitz’s fast-moving tale, difficult to put down, displays the abrupt transformation of Germany’s Jews from citizens to dispossessed, despised aliens.

“We’ve become a business opportunity for our opponents and a danger for our friends,” Otto says. “And in the end, we’re blamed for our own bad luck.”

The author’s luck was bad, too, despite having fled Germany with his mother in 1935 to Sweden, then to France, Luxemburg and, in 1939, to England, where he wrote The Passenger after Kristallnacht. It was published in England and France to scant notice and rediscovered only recently. Revised by publisher and editor Peter Graf according to the author’s wishes, it is translated by Philip Boehm.

When war began, Boschwitz was deported to Australia as an “enemy alien,” then reprieved.

But despite his being only a half-Jew, with England’s help Germany got him after all: Sailing back to England in 1942, his ship was torpedoed. He was 27.

In an insightful introduction, novelist and professor André Aciman points to the author’s uncanny foresight.

“What Boschwitz saw clearly enough was the utter despoilation of one’s identity, of one’s trust in the world, and ultimately of one’s very humanity,” Aciman says.

Pondering the Jews’ predicament, Otto thinks: “Perhaps they’ll carefully undress us first and then kill us, so our clothes won’t get bloody and our banknotes won’t get damaged. These days, murder is performed economically….

“Who could have imagined anything like it? In the middle of Europe, in the 20th century!”

***

Neal Gendler is a Minneapolis writer and editor.