Reviewed by NEAL GENDLER

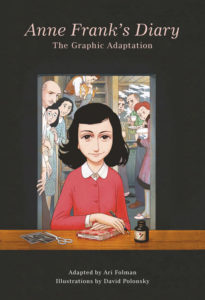

Three concerns arise immediately when confronting Ari Folman’s and David Polansky’s clever, illustrated adaptation of Anne Frank’s diary in a restrained “graphics novel” style.

First: Does this presentation trivialize the Shoah or the Frank family tragedy?

First: Does this presentation trivialize the Shoah or the Frank family tragedy?

Second: Is this truncated form of her story accurate?

Third: Is this book necessary, revealing new information or increasing accessibility to a story already known worldwide?

Folman answers the first two questions in an “adapter’s note” at the end: “We have undertaken this project with the intent to remain true to Anne Frank’s memory and legacy and have weighed our options with care.”

Some might object that presenting Ann’s story in so-called graphic style trivializes it, but Anne Frank’s Diary: The Graphic Adaptation does not. Polansky’s drawing style is lighthearted, more in the manner of a comic strip than a portrait, but the result is charming and serious, not cartoonish. (Two pages have cartoons by Hila Noam.

Judging from photos in a different Anne Frank book, Polansky seems to have captured likenesses well.

Deprivation, brutalization and death of Jews, and the dreariness of eight people confined tightly are portrayed sufficiently. An afterword tells what happened to the “secret annex” occupants and their gentile helpers.

Accuracy was a challenge, Folman says.

“The trickiest task … would be to retain only a portion of Anne’s original diary while still being faithful to the entire work.”

Without having the original at hand, I would say they did so. While many entries had to be “amalgamated,” much of the text comes from the diary, sometimes entire entries — including her last.

Folman and Polansky tried “to visually interpret and preserve her powerful sense of humor, her sarcasm … and her obsessive preoccupation with food.” They depict her periods of depression and despair “as either fantastical scenes (such as Jews rebuilding the pyramids under the Nazi whip) or as dreams.”

Anne, who got along well with her father, but less with Margot and little with her mother, saw herself as constantly criticized. Polansky depicts Anne’s self-images — real and imagined — by borrowing from two famous paintings. One full page shows Anne as the person in Edvard Munch’s “The Scream,” surrounded by criticisms. The opposite page shows her as the woman in Gustav Klimt’s “Lady in Gold,” with hair, face, posture and dress perfect.

Unfortunately, their surprisingly successful approach takes a needless, stupid break. During pages about nerve-wracking, sleep-depriving air raids and prolonged hammering of anti-aircraft guns, one frame shows one of the men looking out a window at a fleet of aircraft, saying: “I love the smell of gunpowder in the morning.”

This utterly inappropriate theft from the movie Apocalypse Now may be meaningless to very young readers and is a jarring, wise-guy, even disgusting interruption for the rest of us.

One can debate the need for this book. Does a graphic version add accessibility or understanding of Anne’s story and the Shoah? It certainly adds accessibility for the intellectually lazy, but for decades, the diary has been on secondary-school reading lists. The story is well known, by reputation if nothing else.

But for some, illustration may convey reality better than words, and Polansky’s product is admirable, including a full-page cutaway drawing of the annex and who slept where.

Folman says the book came from a proposal by the Anne Frank Fonds in Basel, Switzerland. Despite “grave reservations,” he went ahead.

“Rereading Anne’s diary as an adult … it was astounding to me that a 13-year-old girl had been able to take such a mature, lyrical look at the world and translate that into concise, probing entries brimming with compassion and humor, and with a degree of self-awareness that I have rarely encountered in the adult world, much less among children,” he says.

“We are sensitive to and aware of the liberties we have taken,” Folman says. “Our goal was always foremost to honor and preserve the spirit of Anne Frank in each and every frame.”

My initial misgivings were overtaken by the feeling that they succeeded.

***

Neal Gendler is a Minneapolis writer and editor.

Neal,

Thank you for your thoughtful story. I wish you had also mentioned these reference points:

1) Art Spiegelman’s “Maus,” a breakthrough graphic novel that assuredly did not trivialize the Holocaust.

2) Ari Folman directed the extraordinary animated film “Waltz with Bashir,” and is reportedly at work on an animated Anne Frank film. The first is not a kids’ film.

Best,

Michael Fox